this post was submitted on 03 Dec 2023

423 points (100.0% liked)

196

17508 readers

717 users here now

Be sure to follow the rule before you head out.

Rule: You must post before you leave.

Other rules

Behavior rules:

- No bigotry (transphobia, racism, etc…)

- No genocide denial

- No support for authoritarian behaviour (incl. Tankies)

- No namecalling

- Accounts from lemmygrad.ml, threads.net, or hexbear.net are held to higher standards

- Other things seen as cleary bad

Posting rules:

- No AI generated content (DALL-E etc…)

- No advertisements

- No gore / violence

- Mutual aid posts are not allowed

NSFW: NSFW content is permitted but it must be tagged and have content warnings. Anything that doesn't adhere to this will be removed. Content warnings should be added like: [penis], [explicit description of sex]. Non-sexualized breasts of any gender are not considered inappropriate and therefore do not need to be blurred/tagged.

If you have any questions, feel free to contact us on our matrix channel or email.

Other 196's:

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

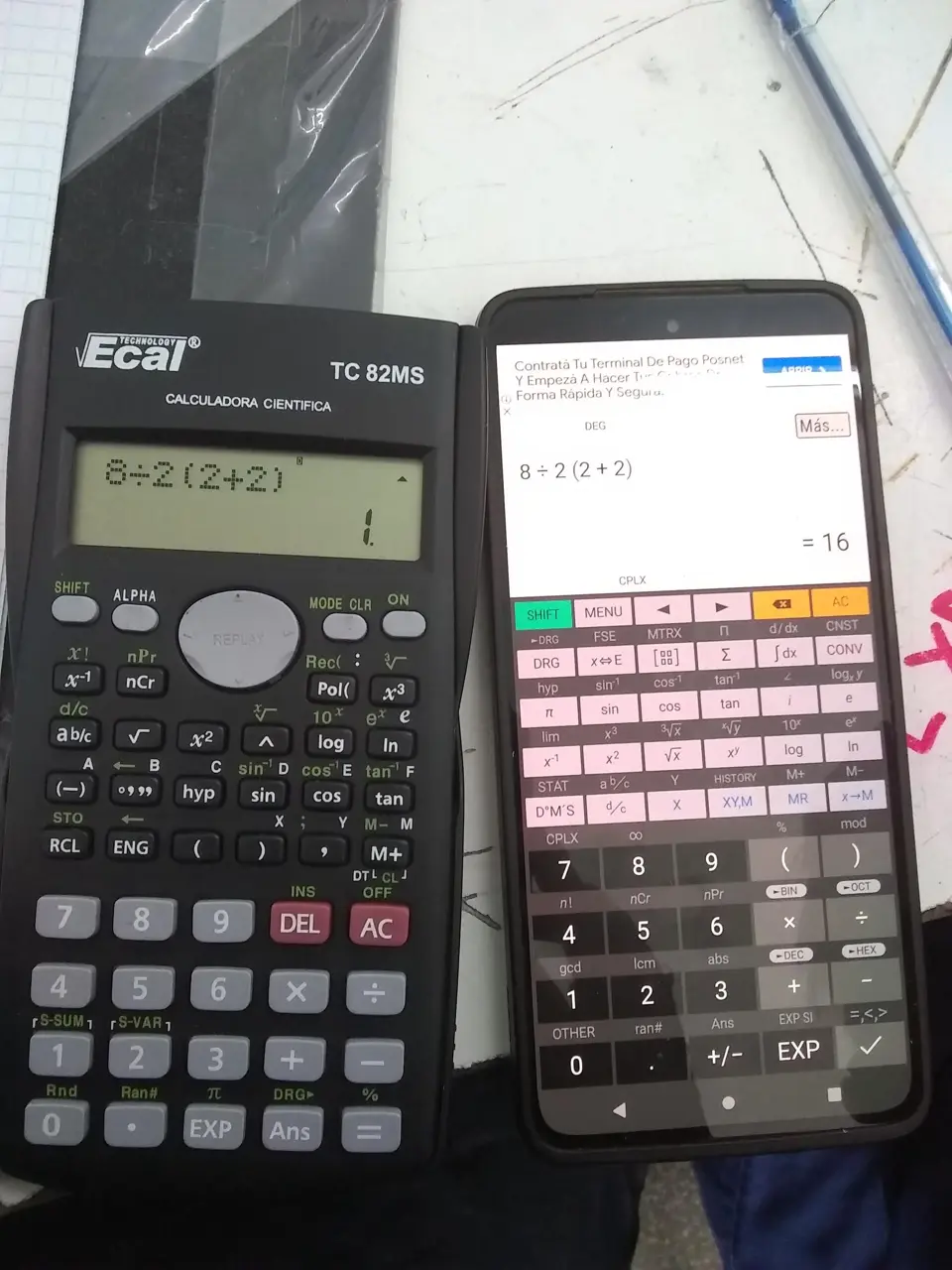

Interestingly I’ve wondered if this is regional, as a fellow Aussie I learned the same as you but it seems in other places they learn the other way

FWIW I went to school in Asia, using an internationally-focused curriculum, rather than going through the Australian curriculum here in Aus.

The video I linked includes some discussion with a calculator manufacturer who apparently is under the impression that teachers in North America are asking for strict BIDMAS, so the calculator manufacturer actually switched their calculators to doing that. Until they then got blowback from the rest of the world's teachers, so they switched back to BIDMAS with juxtaposition being prioritised over division. The video also presents the case that outside of teachers—among actual maths and physics academics—prioritising juxtaposition is always preferred, even in North America.

I'm an Australian teacher who has also taught the U.K. curriculum (so I have textbooks from both countries) and, based on these comments you mention, have also Googled some U.S. textbooks, and I've yet to see any Maths textbooks that teach it "the other way". I have a very strong suspicion that it's just a lot of people in the U.S. claiming they were taught that way, but not actually being true. I had someone from Europe claim the way we (and the U.K.) teach it wasn't taught there (from memory it was Lithuania, but I'm not sure now), so I just Googled the curriculum for their country and found that indeed it is taught the same way there as here. i.e. people will just make up things in order not to admit they were wrong about something (or that their memory of it is faulty).