By Lars Kovennium, Viral Magazine

On the edge of a closed landfill outside Des Moines, a low concrete building hums softly behind a chain-link fence. There are no smokestacks, no flares licking at the sky. Instead, a thick pipe snakes out of the trash mound nearby, carrying methane gas that would otherwise seep into the atmosphere. Inside the building, racks of servers blink steadily, processing cloud workloads, video streams, and machine learning jobs.

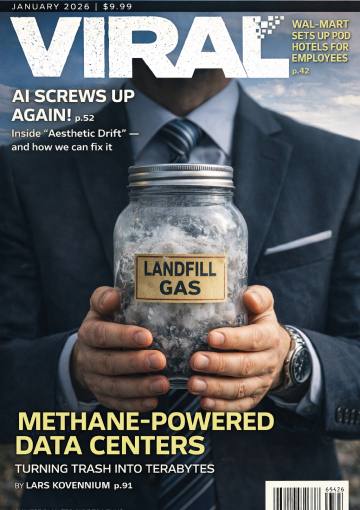

What started as a few small trials has settled into something more permanent, a business built around capturing landfill methane. It’s a business model, and yes, it literally stinks, which in this case is kind of the point.

Over the past two years, a quiet race has emerged among energy startups and infrastructure companies to build data centers powered directly by captured landfill methane. The pitch is simple. Landfills already produce vast amounts of gas as organic waste decomposes. Instead of burning it off or letting it leak, operators can capture it, clean it, and use it to generate electricity on-site. Data centers, with their constant demand for power, become the perfect customer.

“Landfills are one of the most underused energy assets in the country,” said Aaron Delgado, chief executive of GreenStaX Systems, a company operating three methane-powered data centers in the Midwest. “The gas is there every day. Our servers don’t need sunshine or wind or something that smells good. They just need consistency.”

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, trapping far more heat than carbon dioxide over shorter timescales. Environmental regulators have long encouraged landfill operators to capture it, often using it to generate electricity for the grid or for nearby industrial facilities. What’s new is the idea of pairing that energy source directly with computing infrastructure.

Data centers are notoriously power-hungry. As demand for cloud services and artificial intelligence grows, so does scrutiny of the industry’s environmental footprint. Hyperscale operators have pledged carbon neutrality, often relying on renewable energy credits and long-distance offsets. Methane-powered data centers offer something more tangible, at least on paper.

“This is one of the rare cases where waste reduction and digital infrastructure actually align,” said Priya Nandakumar, an energy systems researcher at the University of Illinois. “You’re preventing methane emissions and producing useful work at the same time.”

But the model comes with trade-offs.

The amount of methane a landfill produces declines over time. Gas quality can fluctuate. Equipment must be tuned to handle impurities. And critics argue that tying computing infrastructure to landfills risks locking in waste-heavy systems instead of pushing harder on reduction and reuse.

“There’s a danger of creating a perverse incentive,” said Maria Torres, policy director at the Clean Earth Coalition. “If data centers depend on landfill gas, what happens when we succeed at reducing waste?”

Operators counter that the scale remains limited. Even the largest landfill-based installations are tiny compared to hyperscale facilities run by tech giants. Most are designed for edge computing, content delivery, or specialized workloads that benefit from localized infrastructure.

At a site near Fresno, California, GreenStaX engineers walk through a narrow server room where the air smells faintly of metal and ozone. Next door, a bank of generators converts captured methane into electricity, each unit constantly adjusting to shifts in gas flow. Inside the room, the company has leaned hard into reuse. Racks and control stacks are built from refurbished Commodore 64 and Radio Shack TRS-80 machines, stripped down and rewired to handle auxiliary computation, monitoring, and system control tasks.

It’s not the most efficient setup, engineers admit, and it’s more expensive to maintain than modern purpose-built hardware. But with methane power available around the clock, efficiency is less of a constraint. The old machines hum alongside newer servers, part sustainability statement and part practical experiment in seeing how far reclaimed technology can be pushed when energy is cheap and otherwise wasted.

“It’s not glamorous,” said field engineer Luis Ramirez, pausing to take a long drink from a Mountain Dew before setting the bottle down on a workbench. He glanced at it and nodded toward the landfill outside. “That plastic’s going right back into my paycheck sooner or later. Pretty cool, right?”

Ramirez said the appeal is consistency. “I love AI. It’s not going anywhere,” he added, gesturing toward the servers. “If we’re going to keep building bigger models, we’re going to need power sources like this. Trash doesn’t take days off.”

Municipalities have taken notice. Several cities now include data center partnerships in landfill redevelopment plans, seeing them as a way to generate revenue while meeting emissions targets. In some cases, operators pay landfill owners directly for the gas, creating a new income stream for local governments.

The economics are improving, too. Advances in modular data center design allow companies to deploy smaller, standardized units quickly. On-site generation reduces exposure to grid volatility. And as carbon accounting tightens, avoiding methane emissions carries increasing value.

Still, the future of landfill-powered data centers remains uncertain. As renewable energy storage improves and grid infrastructure evolves, methane may lose its appeal. For now, though, the servers keep running, fueled by the slow decay of yesterday’s waste.

“This isn’t a silver bullet,” Nandakumar said. “But it’s a reminder that the infrastructure of the internet is physical. It has to live somewhere. It has to run on something.”

Delgado takes the idea further. He said he envisions methane-powered data centers operating in towns and cities across the country, wherever landfills already exist. The more sites, he argued, the better. As for the smell, he waved it off. “People get used to it,” he said. “You notice it at first, then it just becomes part of the background. Like the internet itself.”

Behind the fence, the landfill sits quietly, doing what it has always done. This time, at least, someone is listening to the gas it gives off, and turning it into computation. And that smells like money.